When you have read, you carry away with you a memory of the man himself; it is as though you had touched a loyal hand, looked into brave eyes, and made a noble friend; there is another bond on you thenceforward, binding you to life and to the love of virtue.

~Robert Louis Stevenson, "Books Which Have Influenced Me"

Robert Louis Stevenson wrote the beautiful sentence above in reference to the relationship he felt with his favorite authors. It happens to be a great description of how I feel about Stevenson. But there's another literary character I've come to know recently, who fits the bill perfectly as well--Socrates.

Although Socrates did not technically write any of his famous dialogues--his student Plato did--it is still Socrates' personality which dominates the text. Anyone who has even skimmed works like the Republic or the Apology will be familiar with his persona: witty and yet methodical, clear-minded, inquisitive, humble, and never budging an inch from his principles. The most vivid impression I have received of Socrates is one of immense integrity. Here is a lover of truth and virtue the world has seldom seen.

Over the past few months I have been meandering my way through the Republic. Although it's not exactly what you'd call light reading, I have found it surprisingly refreshing. The clarity of Socrates' speech and logic seems a mental cleansing which sets my thoughts in order. Besides that, Socrates' own enthusiasm for the topics at hand is infectious. He livens the long abstract discussions with amusing metaphors like the following, from the fourth book of the Republic. The context: Socrates and his disciple Glaucon have been trying to pin down the essence of justice. On the way they've gotten a bit sidetracked, creating an ideal State. But now Socrates wants to return to the original issue:

The time then has arrived, Glaucon, when, like huntsmen, we should surround the cover, and look sharp that justice does not steal away, and pass out of sight and escape us; for beyond a doubt she is somewhere in this country: watch therefore and strive to catch a sight of her, and if you see her first, let me know.

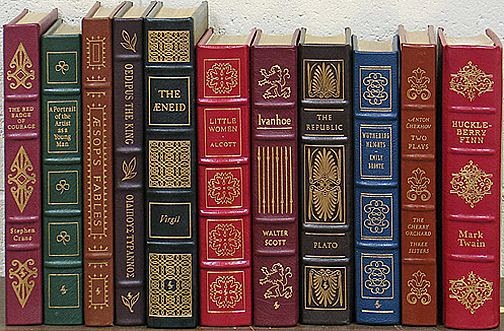

I can picture him speaking, with a twinkle in his eye, like a jovial professor. It's little things like that which distinguish Great Books from textbooks--a Great Book conveys a person.

The longer passage I'd like to share with you today is a bit more serious, but an equally vivid painting of Socrates' personality. A little later on in Book IV, after a long and winding discussion on the nature of justice, education, and the State, Socrates finally lays out his portrait of the ideal just man:

But in reality justice was such as we were describing, being concerned however, not with the outward man, but with the inward, which is the true self and concernment of man: for the just man does not permit the several elements within him to interfere with one another, or any of them to do the work of others,--he sets in order his own inner life, and is his own master and his own law, and at peace with himself; and when he has...become one entirely temperate and perfectly adjusted nature, then he proceeds to act...always thinking and calling that which preserves and co-operates with this harmonious condition, just and good action, and the knowledge which presides over it, wisdom, and that which at any time impairs this condition, he will call unjust action, and the opinion which presides over it ignorance.

I'm afraid I cannot convey the whole genius of this little summary without diving into an explanation of Socrates' definition of justice and his division of the soul into the rational and the passionate. But that second phrase which I highlighted above simply arrested me the moment I read it. In the light of Socrates' piercing insight, I recognized that many of my own anxieties, frustrations, and failings are a result of a disorganized inner life. More often than not my desires are self- and pleasure-centered, when they should be love- and truth-centered. I found the call to set my inner life "in order" an inspiring one. And unlike Socrates' ideal man, I don't have to be "my own master" and "my own law". Considering my imperfections, that's probably a good thing. Instead, as a Christian, I discover both in the Person of Christ.

I hope I have succeeded in conveying at least a little of Socrates' unique personality through these quotes. Reading his dialogues has truly been what Stevenson described: a blessed obligation, binding me to life and the love of virtue.

The time then has arrived, Glaucon, when, like huntsmen, we should surround the cover, and look sharp that justice does not steal away, and pass out of sight and escape us; for beyond a doubt she is somewhere in this country: watch therefore and strive to catch a sight of her, and if you see her first, let me know.

I can picture him speaking, with a twinkle in his eye, like a jovial professor. It's little things like that which distinguish Great Books from textbooks--a Great Book conveys a person.

The longer passage I'd like to share with you today is a bit more serious, but an equally vivid painting of Socrates' personality. A little later on in Book IV, after a long and winding discussion on the nature of justice, education, and the State, Socrates finally lays out his portrait of the ideal just man:

But in reality justice was such as we were describing, being concerned however, not with the outward man, but with the inward, which is the true self and concernment of man: for the just man does not permit the several elements within him to interfere with one another, or any of them to do the work of others,--he sets in order his own inner life, and is his own master and his own law, and at peace with himself; and when he has...become one entirely temperate and perfectly adjusted nature, then he proceeds to act...always thinking and calling that which preserves and co-operates with this harmonious condition, just and good action, and the knowledge which presides over it, wisdom, and that which at any time impairs this condition, he will call unjust action, and the opinion which presides over it ignorance.

I'm afraid I cannot convey the whole genius of this little summary without diving into an explanation of Socrates' definition of justice and his division of the soul into the rational and the passionate. But that second phrase which I highlighted above simply arrested me the moment I read it. In the light of Socrates' piercing insight, I recognized that many of my own anxieties, frustrations, and failings are a result of a disorganized inner life. More often than not my desires are self- and pleasure-centered, when they should be love- and truth-centered. I found the call to set my inner life "in order" an inspiring one. And unlike Socrates' ideal man, I don't have to be "my own master" and "my own law". Considering my imperfections, that's probably a good thing. Instead, as a Christian, I discover both in the Person of Christ.

I hope I have succeeded in conveying at least a little of Socrates' unique personality through these quotes. Reading his dialogues has truly been what Stevenson described: a blessed obligation, binding me to life and the love of virtue.